21 Years as a Systems Engineer: Hard-Won Lessons from the Trenches & Mentors

Image Credit: Roger Filomeno

After spending over two decades building and maintaining large-scale systems, I’ve learned some hard lessons. These aren’t abstract principles; they’re insights from countless outages, design reviews, and production incidents. Here’s what I wish I’d known on day one.

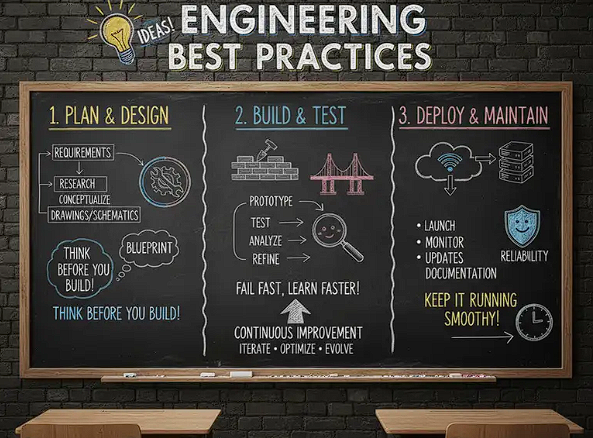

Engineering Best Practices

Write Boring, Readable Code

The most maintainable code isn’t the cleverest—it’s the most obvious. Early in my career, I prided myself on writing succinct, “elegant” one-liners. Then I had to debug one at 3 AM during an outage, and I couldn’t remember what it did. Also I’m talking about you Mark :3

Example: Instead of writing:

result = [x for x in data if x.status == 'active' and x.score > threshold and validate(x)]Write it like a story:

active_items = [item for item in data if item.status == 'active']

high_scoring_items = [item for active_items if item.score > threshold]

result = [item for item in high_scoring_items if validate(item)]When your service is down and customers are impacted, you want code that reads like plain English.

Design for 10x Scale, Not 2x

Every system design should assume it will handle ten times the current load, not just double. This forces you to think deeply about architecture from day one. Reminds me of Friendster Mobile :3

Example: When building a user authentication service handling 1,000 requests per second, don’t just add more servers. Ask: “What happens at 10,000 requests per second?” You’ll quickly realize you need:

- Database read replicas and connection pooling

- Distributed caching (Redis/Memcached)

- Rate limiting and request prioritization

- Horizontal sharding by user ID ranges

This thinking upfront saves you from painful rewrites later.

Prioritize Statelessness and Immutability

In distributed systems, machines fail constantly. If your service stores state locally, you’re asking for trouble.

Example: I once built a session management service that cached user sessions in local memory. When a container crashed, thousands of users were logged out. The fix? Store all session data in a distributed system like Redis or a database. Now any container can handle any request, and failures are invisible to users.

Make your services cattle, not pets—any instance should be disposable and replaceable.

Write Clear Design Documents

Design docs aren’t bureaucracy; they’re thinking tools. Writing forces you to confront problems you’d otherwise discover in production.

Example: Before building a payment processing system, I wrote a design doc that included:

- Problem: Process 50,000 transactions/day with <1% failure rate

- Alternatives: Synchronous vs. asynchronous processing, third-party vs. custom

- Trade-offs: Latency vs. reliability vs. cost

- Failure handling: Retry logic, dead letter queues, idempotency keys

- Rollout plan: 1% → 10% → 50% → 100% traffic over two weeks

The doc surfaced edge cases (duplicate payments, partial refunds) that would have been disasters in production.

Treat API Stability as a Sacred Contract

When hundreds of services depend on your API, breaking changes are catastrophic. I learned this the hard way when I renamed a field and broke 47 internal services overnight.

Example: If you have an API endpoint:

{

"userId": "123",

"name": "Alice J. Doe",

"email": "[email protected]"

}And you want to add address info, create a new version:

// v2 - backward compatible, v1 still works

{

"userId": "123",

"name": "Alice J. Doe",

"email": "[email protected]",

"name_parts": { // New optional field

"first_name": "Alice",

"middle_name":"Johansen",

"last_name":"Doe"

}

}Never remove fields or change types without a major version bump. Deprecate old versions slowly, with months of warning.

Test Behavior, Not Implementation

Tests should verify what your code does, not how it does it. This makes refactoring safe.

Example: Bad test (brittle):

def test_user_service():

service = UserService()

assert service.cache is not None # Tests internal structure

assert service._validate_email("[email protected]") == TrueGood test (robust):

def test_user_service():

service = UserService()

user = service.create_user("Alice", "[email protected]")

assert user.name == "Alice"

assert user.email == "[email protected]"

retrieved = service.get_user(user.id)

assert retrieved == user // Tests behaviorWhen you refactor the caching implementation, the good test still passes.

Use Deterministic Builds

Your build should produce identical results whether it runs on your laptop, a colleague’s machine, or CI. This requires explicitly declaring every dependency and version.

Example: Instead of pip install requests (which might install different versions), use:

requests==2.28.1

urllib3==1.26.12

certifi==2022.9.24With tools like Bazel or Docker, you can ensure that the same inputs always produce the same outputs. This makes large-scale refactors safe—you can verify that millions of lines of code still compile and work identically.

Resilience and Performance

Assume Failure is the Default State

In large distributed systems, something is always broken. Design for it.

Example: When calling a payment gateway API:

def charge_customer(amount, max_retries=3):

for attempt in range(max_retries):

try:

response = payment_api.charge(amount)

if response.status == 'success':

return response

except TimeoutError:

wait_time = (2 ** attempt) + random.uniform(0, 1) # Exponential backoff with jitter

time.sleep(wait_time)

# After retries fail, degrade gracefully

send_to_dead_letter_queue(amount)

notify_ops_team()

return ErrorResponse("Payment processing delayed")Never assume a network call will succeed. Always have a plan B.

Design for Graceful Degradation

When your system is under stress, degrade functionality rather than fail completely.

Example: An e-commerce site under load might:

- Serve product pages from cache (slightly stale data)

- Disable personalized recommendations (show generic popular items)

- Simplify the checkout flow (remove optional fields)

- Show “high traffic” banners to set expectations

Users get a slower experience, but they don’t get error pages. Revenue keeps flowing.

Optimize for P99 Latency, Not Averages

Your slowest users are the ones who suffer. In systems with many microservices, tail latency compounds dramatically.

Example: Imagine a webpage that calls 10 microservices:

- Each service has P50 latency of 50ms (fast!)

- Each service has P99 latency of 500ms (slow!)

At P99, the user waits for the slowest service. With 10 services, there’s a high probability at least one is slow, making the page consistently sluggish for some percentage of users.

Solutions:

- Set aggressive timeouts (e.g., 200ms)

- Use “hedge requests” (send duplicate requests to different servers, use whichever responds first), See Hedging vs Coalescing

- Cache aggressively at the edge

- Budget your latency carefully across services

Even a 100ms slowdown can translate to millions in lost revenue for large platforms.

Cultural and Team Practices

Use Blameless Postmortems

When things break—and they will—focus on systems, not scapegoats.

Example: A junior engineer pushed a config change that took down the site for 20 minutes. The postmortem didn’t ask “Who messed up?” Instead:

Root cause: Configuration change wasn’t validated before deploy Contributing factors:

- No automated validation in CI/CD pipeline

- Insufficient staging environment testing

- Unclear rollback procedures

Action items:

- Add config schema validation

- Create production-like staging environment

- Implement one-click rollback

- Update runbook with clearer steps

The engineer felt supported, not attacked. The team got more resilient systems.

Value Kindness, Humility, and Collaboration

The best engineers I’ve worked with weren’t the smartest—they were the kindest.

Example: A senior engineer spent 30 minutes explaining how our distributed tracing system worked to me when I was struggling. He drew diagrams, shared runbooks, and followed up with helpful links. He could have said “just read the docs,” but she invested in my growth.

This culture of helpfulness compounds. When you create an environment where asking questions is celebrated, not punished, everyone learns faster. The most productive teams I’ve been on had strong psychological safety—people admitted when they didn’t understand something, and others jumped in to help.

Final Thoughts

These lessons represent thousands of hours of debugging, countless design reviews, and more than a few 3 AM outages. They’re not about being clever; they’re about being reliable, maintainable, and humane.

The best code is boring. The best designs assume failure. The best teams support each other.

If you’re early in your career, I hope these lessons save you some pain. If you’re a veteran, I hope they resonate. And if I’ve missed something important, I’d love to hear what lessons you’ve learned in the trenches.

Here’s to building systems that work, teams that thrive, and code that doesn’t make you cry at 1 AM.

All code samples are mocked, pls dont use them in productions :3.

Last modified: 23 Jan 2026