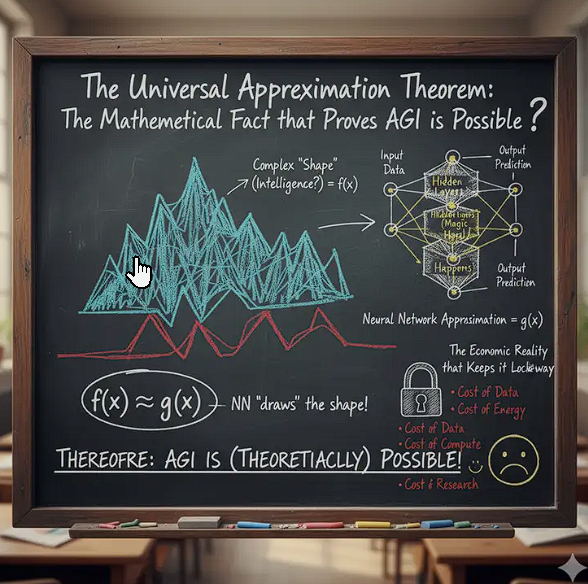

The Universal Approximation Theorem: The Mathematical Fact that Proves AGI is Possible, and the Economic Reality that Keeps it Locked Away

Image Credit: Roger Filomeno

Author’s Note: This article was written with AI assistance, but the ideas and arguments presented are originally from the author.

The Universal Approximation Theorem (UAT) provides the theoretical basis for Artificial General Intelligence (AGI). It states that a neural network with sufficient size and non-linearity can approximate any complex function.

The Undeniable Fact of the Universal Approximation Theorem

The UAT justifies the performance of Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs). It assures us that if a network uses non-polynomial functions (like ReLU or sigmoid) and has sufficient depth, it possesses the capacity to model complex non-linearities. The hypothetical function representing AGI, however complex, exists within the realm of functions an ANN can approximate.

The Critical Flaw: Existence vs. Constructibility

If perfect approximation is possible, why haven’t we achieved AGI? The UAT is an existence theorem, not a constructive one. It guarantees the optimal parameters exist but offers no procedure for finding them.

The quest for AGI faces two constraints:

- The Search Space: Finding parameters requires iterative trial-and-error optimization algorithms like backpropagation to navigate a complex parameter space.

- The Exponential Cost: The resource cost for arbitrary accuracy scales exponentially with dimensionality, known as the Curse of Dimensionality. Deep networks offer efficiency gains, but the total expenditure remains high.

The challenge is computational tractability, not theoretical capacity.

The Real Barrier to AGI is Economic, Not Technical

The ultimate constraint is market economics. Research demands massive capital, so commercial AI efforts prioritize solutions with guaranteed returns—niche problems like grammar correction or HR management. Projects pushing AGI boundaries are often limited to massive tech conglomerates, sometimes more for marketing than application.

The final 1% of progress is buried under an exponential wall of computational cost. The question is whether to expend vast resources now or wait for efficient techniques.

The Generation Ship Analogy

Consider a generation ship launching with inefficient chemical rockets, risking being overtaken by a later ship with faster technology. Current AI expenditure—GPUs, cooling, data storage—risks being that generation ship: inefficiently burning resources for an approximation that might soon be obsolete.

We may be overestimating our capability to bridge the gap in this generation based on financial and resource costs.

The Final Question

The pursuit of AGI demands cautious resource management. A single novel technique or architectural tweak could render today’s costly exponential struggle trivial. The question remains: does the end justify the means to achieve AGI with current technology?

Last modified: 23 Jan 2026